SANTA MARIA DELLA CROCE

Sacred art, history and culture in one of Apulia’s oldest churches

The Church of Santa Maria della Croce, commonly known as “Casaranello”, is one of Apulia’s oldest religious buildings. Renowned for its marvelous mosaics, it is a point of reference for the study of mosaic decorations in Paleochristian churches and presents connections with Greece (Thessaloniki) and Byzantine Italy (Ravenna, Rome, Albenga).

Further to the refined decorative quality of its mosaics, “Casaranello” is renowned for its Byzantine paintings dating back between the 10th and 12th century and for its decorative cycles, realized in late Swabian age (mid-13th century). Further decorations were realized in the late middle Ages, together with some architectural changes. The post-medieval age left traces of some more rustic paintings.

HISTORY

Ten centuries of Christian history

There is widespread dissent about the origins of the sacred building today dedicated to “Santa Maria della Croce” and popularly known as Casaranello. The church is situated in the ancient roman settlement of Casarano parvum, a name found in the Angevin archives, as opposed to the fief of Casarano magnum. These were two separate fiefs with two different priests but with a common administration.

Casaranello boasts very ancient origins and probably dates back to the 5th-6th century. The traditional historiography agrees that the church dates back to the mid-5th century, but recent studies – among which the one conducted by Falla Castelfranchi (2004) – suggest that the dating should be postponed of a century, on the presumption of stylistic comparisons between the mosaic decoration and the architectural features. The mature and sophisticated style of the building, together with the use of the pendentive as element of connection to the dome – hard to be found in a building from the first half of the 5th century – and the presence of a rectangular apse, suggest more likely that the church dates back to the mid-6th century. The monument was probably part of the property of Massa Callipolitana and even later on it continued to gravitate in the territory of the diocese of Gallipoli.

Also the original function of the building is still uncertain. It is excluded that it was a martyrium, hence it might have been used as baptismal church, i.e. one of those buildings realized in order to fulfill the needs of the rural population. However, it is not excluded that the church might have had another function, namely to preserve a sacred relics, the cross. This would justify the presence of the cross in the dome and the very name of the church (Falla Castelfranchi, 2005).

There are no decorative traces dating back to the early Middle Ages; hence it is not certain whether the church used to be attended in that age. Further decorations date back to the 10th century: the first frescos, containing Greek and Byzantine inscriptions, were realized in this age. From the middle Ages until the end of the 14th century, Casaranello continued to play a significant role in the southern part of Terra d’Otranto. This is testified by the frequently renewed decoration, often updated to the modern stylistic and iconographic trends. In fact, the sacred building hosted at least a cycle of paintings for each century.

In the late Middle Ages the church underwent some architectural changes, mostly on the façade, whereas in the first half of the 16th century it experienced a new and more popular decorative cycle. In the following century, moreover, the church temporarily took the name of “Santa Maria de Idri” (probably a malapropism of the name “Santa Maria Odegitria”) and it hosted two further altars, today unfortunately lost.

During modern age the life of Casaranello was bound to its little fief and hence fell into oblivion, deteriorated and was even used for inappropriate functions.

The church was rediscovered at the beginning of the 20th century by the scholar Haseloff, which in one of his essays described it as the oldest and most important monument in the primitive Christian age of the south-east of Italy.

ARCHITECTURE

The Church of CasaranelloThe church was built with blocks extracted ad hoc rather than with second-handed ones and today boasts a large façade, animated by a single entry door with a lunette and a little sculpted rose window, which dates back to the late middle Ages; two rectangular windows are present sideways, in correspondence of the lateral lunettes. The statues of St. Lucy and St. Catherine, similar to two acroteria, are placed above, on the two lateral extremities.

A second entrance is present on the north side of the church, whereas on the southern part of the transept stands out the belfry, unusually placed further backwards than the aisles. Both elements were realized in later modifications.

The high quality of the walls is proven not only by the aforementioned lack of second-handed blocks, but also by their remarkable dimension and by the presence of the ferrules: these were realized in fine and well-cut blocks and recall the clay ferrules present in the façade (in the central portion), in the lateral arcades and in the presbytery’s windows.

The interior is divided into three naves separated by pillars connected to one another by wide arches. The transept does not extend sideways or in height and it leads towards the only apse, which is more extensive and presents a rectangular base. This type of apse was not common during the Paleochristian age. Similar examples can be found in Centoporte in Giurdignano, in the ruins of the small church of St. Donato in Taurisano and in the church of St. Eufemia in Specchia Preti.

According to Falla Castelfranchi (2004; 2005) the sacred building originally had a basilica plan divided into pillars, whereas Prandi suggests a Greek-cross plan with further expansions of the nave in the 13th century and the addition of the aisles in the 14th century. This last suggestion was proved wrong by the restorations of the ‘70s. After the restoration and thanks to an analysis conducted on the walls, Bucci Morichi (1988) confirmed that the actual dimensions of the building correspond to the original ones. Nevertheless, he suggested an original plant with a single nave, while the aisles must have been added in the early middle Ages. According to Trinci Cecchelli (1974), the discovery of a mosaic portion in the nave – probably dating back to the origins of the church – proves wrong the hypothesis of an original Greek-cross plan. The mosaic represents three concentric rows of circles, one dark, one red and another dark one. The circles are placed one next to the other, intersecting one another and they must have contained some decorative motifs today no longer visible.

It is uncertain which kind of ceiling was conceived for this monument, if a pitched roof or a barrel vault: the experts rather agree on the second option, considering the thickness of the walls (62-63 cm).

As suggested by Falla Castelfranchi (2005), architecture and decoration work in perfect harmony, which is why the mosaics and the monuments hosting them must always be considered together.

THE MOSAICS

The Church of CasaranelloPALEOCHRISTIAN (5th-6th century)

Wonderful mosaics cover the cupola, the bema’s barrel vault and the apse. They represent one of the oldest mosaic decorations in the region (Falla Castelfranchi 2005), together with the ones of the baptistery of Canosa, of San Giusto a Lucera and of the Cathedral of Siponto. As of today they represent the only preserved late-antique wall mosaic of ancient Calabria.

The dating of the mosaic is uncertain, but considered that it is linked to the origins of the church it should be between the 5th and the 6th century. According to Falla Castelfranchi (2004; 2005) the iconographic program used to be articulated in two different registers: a non-figurative one in the cupola and on the barrel vault and a figurative one in the apse, where the most meaningful images of the iconographic program are portrayed. This structure is similar to other mosaic decorations, such as the Severian baptistery in Naples (end of the 4th century) and the mausoleum of Galla Placida in Ravenna (mid 5th-century). The tiles are made of different materials, i.e. white marble, glass and clay, often used to portray the complexion of the faces and inspired to the models used for the floor. Also according to Trinchi Cecchelli (1974) the use of cotto tiles indicates that the dating should be postponed to between the 5th and the 6th century.

THE APSE

The apse

In the centre of the upper part of the bottom wall of the apse one can catch sight of a portion of a red nimbus against a blue background: as already speculated by Bartoccini (1934), this must have been a Virgin with Child, either standing or sitting on a throne. Similar examples are already present in Puglia, i.e. in Canosa (late 5th century – first half of the 6th century) and in the Cathedral of Trani, where the Virgin with Child is portrayed together with two of the three wise men offering their gifts.

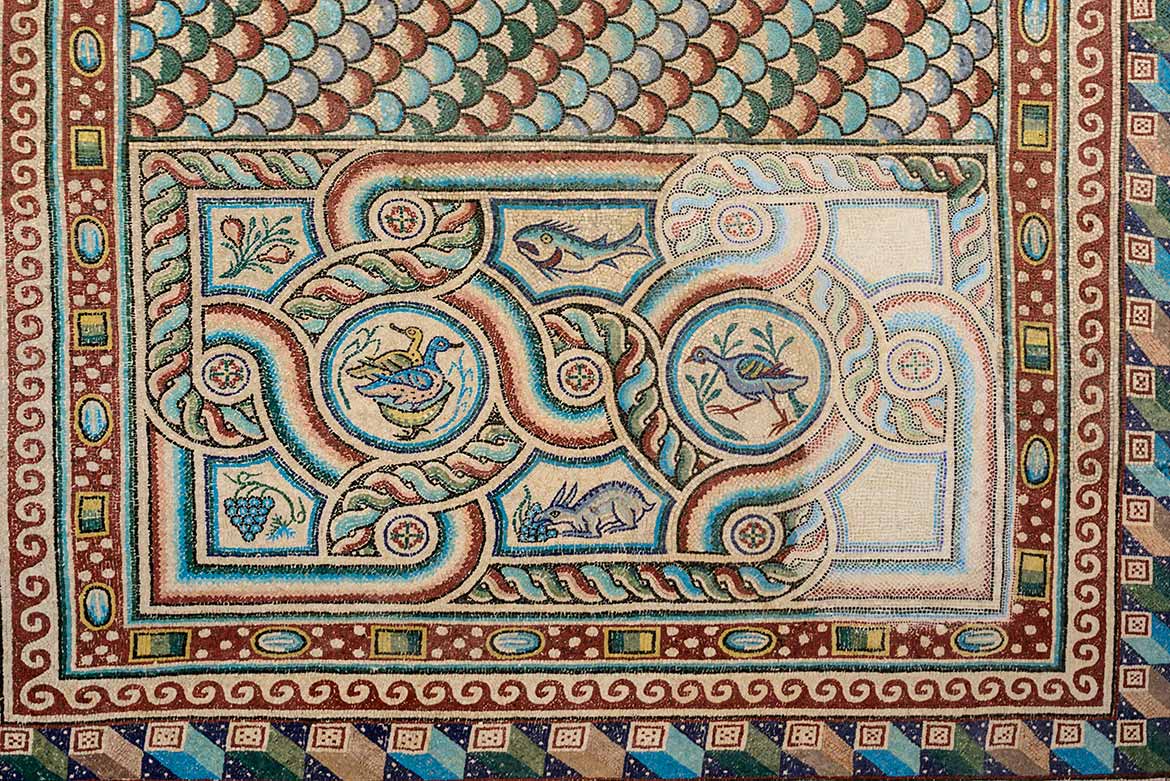

In the bema’s barrel vault, the surviving mosaics give life to beautiful shades of color. The mosaics stand out in multiple frames intertwined in two symmetrical squares hosting zoomorfic and flower motifs, not always easy to identify. In the left box, Trinci Cecchelli (1974) recognizes a twig with red-pink pears, a light blue grape, two ducks crouched on a golden flower, a green fish, a rabbit or maybe a hare crouched down while biting a grape, a cockerel scampering between two twigs. Other frames don’t present figurative motifs. In the right sector, looking the apse, one can identify three grey-blue broad beans, an artichoke, a hen, a crouched down hare biting a grape, a bird similar to a goldfinch with a long tale between two twigs, a grape and a blossomed twig, maybe a laurel oak. On the keystone appears the motif of the opus pavonaceum, formed by colored tiles overlapping one another as in a peacock’s tale (Pisanò 2003). Five decorative stripes are placed on the bottom, livened up by various elements.

THE CUPOLA

The cupola

The cupola is dominated by a starry vault, at the centre of which stands out a cross made of gold tiles. Twigs intertwine with feathers on a white background and the scene is pervaded by a pale blue light. There is no doubt on the fact that the cupola has a symbolic and theological meaning. The background against which the cross is portrayed fades through three ranges of light blue, becoming a symbol of the trinity. Similar examples can be found in Albenga and in the mosaic with the transfiguration in Sinai (around 550). Lower down, a colorful strip separates the sky from the vegetal motifs, composed by spirals animated by pomegranates, pears and grapes. In three out of the four plumes an ivy leaf appears, in the fourth a motif – probably zoomorphic, according to Pisanò a jellyfish (2003). Lower down, a decorative frame grafts from festoons, reflecting the one in the barrel vault.

The closest comparisons were between the mosaics of Casaranello and those present in two churches in Thessaloniki: Saint George (early 6th century) and Acherotipa (mid-5th century). Due to the widespread use of white marble tiles, together with light blue tiles, these mosaics resemble those present in the baptistery of Albenga, in Liguria, but also the one present in the aedicule of Cimitile, an artwork dating back to the 6th century, in which the twigs are portrayed on a golden background.

THE FRESCOS

The Church of CasaranelloMIDDLE-BIZANTINE AGE (10th-11th century)

Virgin with Child

The oldest decorative cycle dates back to the late 10th century, as testified by some successful comparisons with other partly dated frescos (e.g. the ones in Carpignano Salentino, dating back to 959 and 1020). This was also confirmed by the paleographic and textual analysis of the survival inscriptions conducted by Jacob (1988), which date back to between 10th and 11th century.

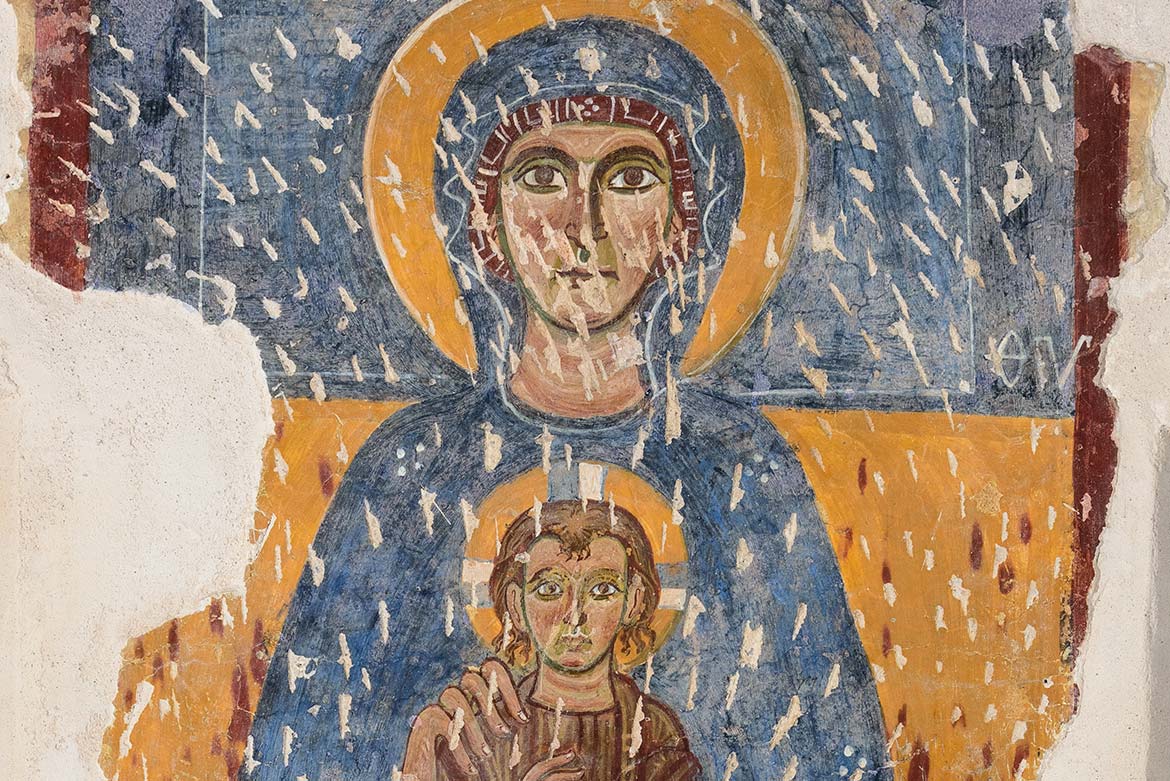

Some inscriptions are engraved on the fresco portrayed on the nave-facing side of the last left pillar, where a Virgin with Child is portrayed. Jacob (1988) suggests that in that age the church was probably already entitled to the Virgin: this is testified by an inscription on the right referring to the consecration of the church to Theotokos, in the presence of an Archbishop of Gallipoli. The fresco is pervaded by sacredness and represents one of the highest expressions of the Byzantine paintings: this is testified by the lack of time and space and by the Greek benediction of the Child. The two figures are aligned: the Virgin displays the Son as if he were a weightless shrine.

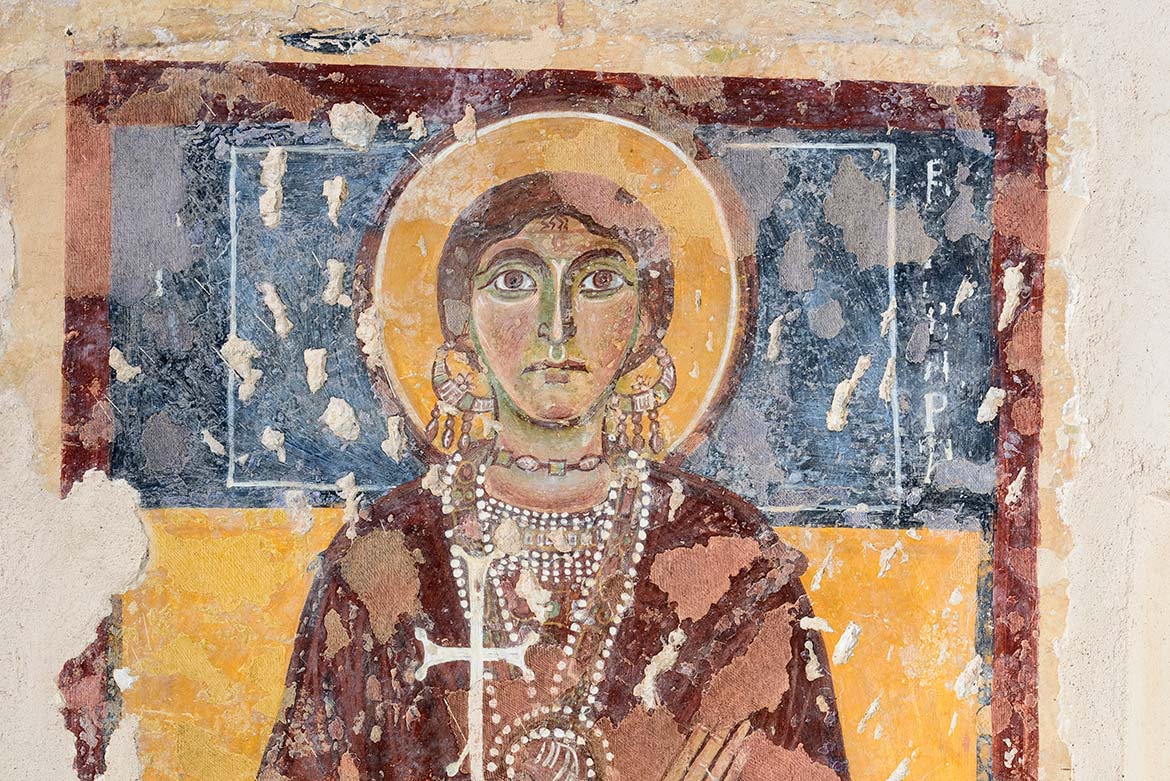

A fresco of Santa Barbara, as indicated by the exegetical inscription, appears on the frontal pillar – the last one on the right. The fresco belongs to the same cycle as the previous one, but it was probably realized by a different artist. Santa Barbara wears the usual sumptuous Byzantine garment and showy earrings: the viewer’s attention is caught by her face, realized by soft brush strokes and light sparkles wisely distributed so as to highlight the main characteristics (Falla 2004).

The apsidal diptych on the left has been identified recently and it should belong to the same cycle. It represents two Saints, both indicated with votive Greek inscriptions. The two paintings were committed by Giorgio and Demetrio: the saint on the left is an archbishop and should be identified as San Nicola; the Martyr Saint next to the archbishop on the apse, according to Falla Castelfranchi (2004) should be confronted with the headless saint portrayed on the right wall on the church of San Pietro in Giuliano di Lecce. According to the survival letters of the exegetic inscription, it could be San Demetrio. Under this layer of painting one can catch sight of another painting, probably from the previous century.

The traces of painting on the first two nave-facing pillars might date back to the same age: the saint on the left should be San Michele, portrayed with the appearances of archistrategos while holding the labarum and wearing the loros; frontally, the few fading traces might represent San Gabriele. In the counterfaçade, on the feft, is portrayed a Saint with some bread: probably Santa Parasceve, according to confrontations realized with other byzantine paintings (Sabato 2011).

It is unknown whether a Christological cycle was portrayed on the walls of the nave already in this age. This hypothesis is not wrong considered that, after the recent restoration a further layer of painting came to light under the fragmentary Christological cycle of the nave.

LATE MIDDLE AGES (12th-13th-14th century)

The continual renewal of the painting decoration, often conducted a few years one after the other and always updated with the new stylistic and iconographic tendencies, testifies to the role of the church as a sort of paradigm and anthology of the medieval painting in Terra d’Otranto.

A further decorative cycle concerning some Christological images on the walls of the nave took place during in the mid-12th century. It is quite curious that these scenes – only four of which are still visible today – don’t develop from the right to the left: the first two, namely The Crucifixion and Juda’s Kiss, are placed counterclockwise on the left wall of the nave and the other two proceed to the right wall, probably The Holy Women at the Sepulcher (hardly readable) and a monumental Anastasis, with Salomon and David hardly visible on the right, under a sort of tent, with their ancestors on the left (Falla Castelfranchi 1991). The empty spaces and the dimensions of the survival scenes might indicate that the cycle used to contain twelve scenes, the typical cycle of the dodekaorton.

After recent restorations it became clear that the byzantine Christological cycle has been overlapped by the famous late Swabian fresco on the martyrdom of the Santa Caterina and Santa Margherita, particularly worshipped in this age. Characterized by an intense expressivity, typical of these narrative cycles, they totally enter in the late-Swabian artistic context. This was also stated by Leone de Castris (1986), who dated them in the years 1250-1260. Probably in the same time when these stories were painted, a second artist was engaged in the decoration of the apse, adding a third layer to the two figures of the Byzantine Saints on the left. This panel represents a Deisis and today hangs on the wall of the right aisle (Falla Castelfranchi 2004).

From an iconographic point of view, this image represents a sum of varieties of the typical Deisis: Battista is replaced with a younger and beardless saint, probably Giovanni Evangelista; Jesus Christ is sitting on a throne instead of standing; the presence of a fourth character, a Saint holding a cross in her hand, unbalances the original ternary ductus of the composition. She was probably a Saint who was particularly worshipped in this church. The dating of the panel between the mid- and the second half of the 13th century is also confirmed by comparisons between the head and the face of Christ of the Anastasis, in the church of Bojana near Sofia, Bulgaria, dating 1259. Nevertheless, the style of the two paintings is different: picturesque in Bojana, rather simple and flat in Casaranello (Franca Castelfranchi 1991).

In the right aisle, nearby the entrance to the sacristy, one can find the hanging panel of the Virgin with Child, once placed on the main altar. According to Prandi (1961) this painting belongs to the series of Byzantine icons from Apulia dating after late 14th century; however, the additional layers of painting make the dating even more difficult. The Virgin gives a flower to the Child, but what draws attention are the eyes of the Protagonist, so full of sadness and melancholy. On the right bottom there is the artwork’s commissioner in praying attitude.

The fresco of Urbano 5th once overlapped the one of Saint Barbara and today hangs on the right aisle. The Pope is sitting on the throne, as proven by the cope which is slightly folded on the wrists and on the knees. The only visible part of the throne is the pinnacled canopy, which presents an acute-arched opening with intertwined lobes in typical late-gothic style. Between the upper part of the arch and the slopes of the pinnacle, the painter wanted to reproduce a skylike motif. The identity of the saint was confirmed by the presence of the heads of the Saints Pietro e Paolo on a tray.

POST-MEDIEVAL AGE (16th-17th century)

Sant’Antonio Abate

During the 16th century the church was enriched by new paintings, such as the fresco of San Bernardino da Siena – a Franciscan saint whose presence in Nardò was testified in 1433. Once placed in the inner side of the first right arch, the fresco hangs today in the counter façade. The saint is portrayed medium close-up, in his typical physiognomy, while holding the trigraph.

The church hosts an additional small diptych which dates back to 1538 and is today placed in the right aisle. It represents the Saints Eligio and Antonio Abate, both portrayed with the typical iconography: the first one with the archbishop clothes, the blacksmiths utensils and some animals to be shoed; the second one wearing monk clothes and leaning on a T-stick, with a small donkey on the bottom. The same cycle includes the fragment of the Franciscan saint placed on the counterfaçade (Sant’Antonio or San Francesco).

A rustic painting dated 1643 is visible on the left aisle: it represents a Virgin with Child and recalls the model of Galaktotrophousa.

Texts: Ass.Culturale ArcheoCasarano “Origini e futuro”

Photos: Marco Santi Amantini

Bibliography: -Bartoccini 1934, “Casaranello e i suoi mosaici”, in Felix Ravenna, n. s., fasc. 3, 45, pp. 157-185 -Bovini 1964, “I mosaici di Santa Maria della Croce di Casaranello”, in Corsi di cultura sull’arte ravennate e bizantina, XI, pp. 35-42 -Bucci Morichi 1988, “Casaranello (Le), Chiesa di Santa Maria della Croce” in Restauri in Puglia 1971-1983, II, Fasano, pp. 402-407 -De Gruneisen 1906, “Studi sulle pitture medievali romane”, in Archivio della R. Società Romana di storia patria, XXXIX, 1906, pp. 518-521 -Falla 1991, “La pittura bizantina nell’età sveva e angioina. Prima parte (XIII secolo)”, in Pittura monumentale bizantina in Puglia, pp. 144 e ss. -Falla Castelfranchi 2004, “La chiesa di Santa Maria della Croce a Casaranello”, in Puglia Preromanica, Jaka book, Milano, pp. 161-175 -Falla Castelfranchi 2005, “I mosaici della chiesa di Santa Maria della Croce a Casaranello rivisitati”, in Atti del X colloquio dell’associazione italiana per lo studio e conservazione del mosaico, Scripta manent, Tivoli, pp. 13-24 -Haseloff 1907, “I mosaici di Casaranello”, in Bullettino d’arte, Bestetti e Tuminelli, Roma, n° 12 dicembre 1907, pp. 22-27 -Jacob 1988, “La consecration de Santa Maria della Croce à Casaranello et l’ancien diocèse de Gallipoli”, in Rivista di studi bizantini e neoellenici n° XXV, La Sapienza, Roma, pp. 147-163 -Leone De Castris 1986, Pittura del Duecento e del Trecento a Napoli e nel Meridione, a cura di Castelnuovo, Electa, Milano -Prandi 1961, “Pitture inedite di Casaranello”, in RIASA 1961, pp. 227-292; ripubblicato in Paesi e figure del vecchio Salento I, pp. 273-327, 1980 , tipografia Polisud-Barra, Napoli -Pisanò 2003, Chiesa S. Maria della Croce – Casarano, Stampa Agam, Cuneo, allegato a Famiglia Cristiana -Sabato 2011, “La decorazione pittorica” in Nociglia. Chiesa Santa Maria de Itri, a cura di Sergio Ortese, Lupo editore, Copertino, pp. 17-48 -Trinci Cecchelli 1974, “I mosaici di Santa Maria della Croce a Casaranello” in Vetera Christianorum II, pp. 167-186 -Wilpert 1917, Die romischen mosaiken und malereien der kirchlichen bauten vom IV bis XIII. Jahrhundert, Friburgo, III, p. 18, TAV. 108